People in Dover want the boats to stop. But they have not met Rishan

- [email protected]

- 0

- Posted on

Dover: The bus driver has a simple answer when asked what he thinks about the asylum seekers who cross the English Channel each week in the hope of a better life in Britain.

“Too many do-gooders,” he says, as we stand near the docks in the port city of Dover.

He is not angry about it, but he wants the boats to stop. And he thinks those who help the asylum seekers are only making things worse. The solution, in his view, is to make it harder for anyone who attempts the crossing from France.

A UK Border Force vessel brings migrants intercepted crossing the English Channel into Dover port this month.Credit: Getty Images

The Dover seafront is mostly empty when I arrive on a weekday morning to ask residents how they feel about the asylum seekers. One woman, out for a walk by the water, thinks some are genuine refugees but most are economic migrants. Another believes there are too many criminals among them.

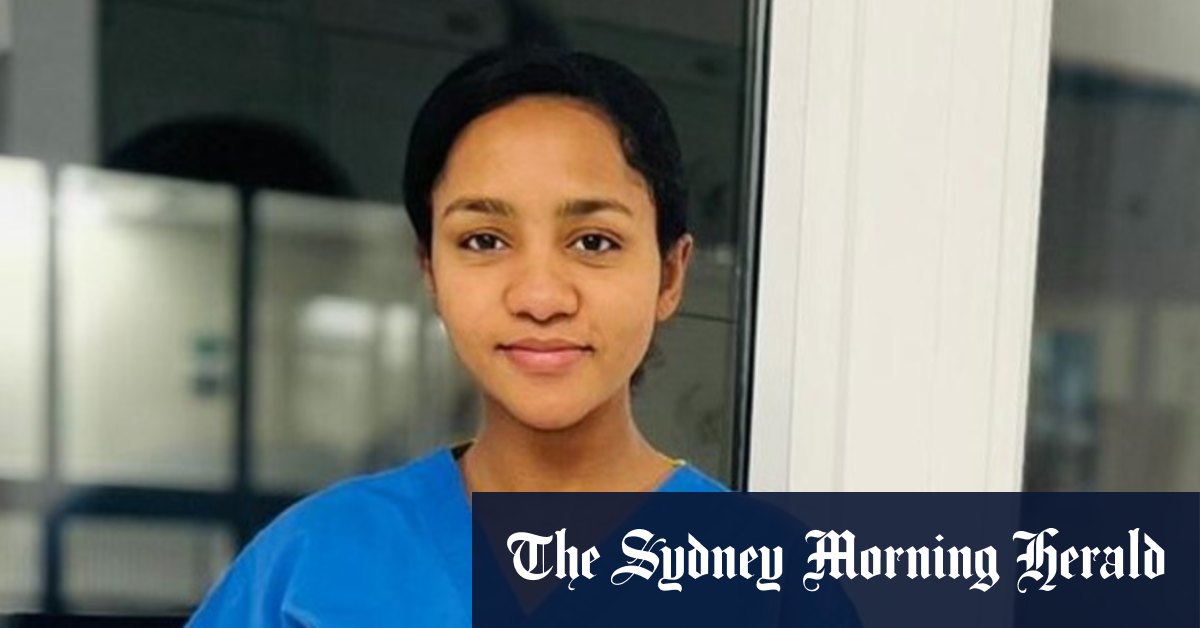

But they have not met Rishan from Eritrea. They might, however, if they ever need a nurse in Canterbury.

Rishan, now living about 25 minutes away from Dover, crossed the channel when she was 17. That was a decade ago, and she made the trip in the back of a truck, not on an inflatable boat. Even so, she puts a human face on the agonising British argument about stopping the boats.

Her family left Eritrea to flee the dictatorship there when she was young, and she was raised in Sudan without any citizenship or prospects. She feared being taken by the police.

“One day, I left home without telling my family. I made a decision: I don’t want to live like that,” she tells me.

Rishan crossed from Sudan to Libya, where she had to wait for four months. She found a boat that would take her north, and was one of the thousands intercepted each year by the Italian authorities. She landed in Sicily and headed north again, sometimes helped by charities. She lived on the streets and hid in trains.

Rishan, 27, a nurse in Canterbury who arrived in the UK as an asylum seeker when she was 17.Credit: Kent Refugee Action Network

“The journey was awful because it was so traumatising. The adrenaline would keep you going, on and on,” she says.

“Especially in Calais. Nobody approached me to say, ‘would you like to apply for asylum?’ because I didn’t know how the asylum process worked. They pushed us from area to area.”

After a month at the French port, she gained a place in the back of a truck – “my small size helped me” – and made it across the channel on a ferry. Hundreds have died in these trucks, suffocated or frozen, but this has not deterred asylum seekers.

Rishan can talk about her escape to England because she gained refugee status after several years. It took her from December 2014 to June 2015 to cross northern Africa and Europe, then years more to find her way in her new home.

As a minor, she was placed with two foster families until she was 21. In her first months, she says, she stayed in her room most of the time. “I wasn’t sure who to trust.” In her second home, she was part of a large extended family with two other young asylum seekers in a house with a loving grandmother. “She was amazing. I loved her and I loved the whole family.”

Loading

Rishan speaks now as a media ambassador for the Kent Refugee Action Network, a charity that helps young unaccompanied refugees and asylum seekers. It had 350 cases last year and offered 45,000 hours of teaching time.

What frustrates her is that the media coverage rarely puts a human face on those who have the potential to contribute to Britain.

“Innocent people cross here to seek safety, and it is just put down as the number of illegal people. They are fleeing persecution, which is well known in countries like Eritrea or Sudan,” she says.

“It puts so many negative things around them, so people think of them as criminals.

“People think that when we come to the country, everything is sorted for us – housing, or benefits. That’s completely the wrong message.

“I always believed it was one journey to come to the UK, but it was another journey to live here and become part of the culture, and learn the language. It took me nine years just to finish university.”

Rishan started work as a nurse last September at a local hospital. One of her fellow refugees has graduated in business management, one is doing occupational therapy, and another has finished a computer science course. Others are in construction.

An aerial view of inflatable craft, used by migrants to cross the channel, stored at a Border Force facility in Dover.Credit: Getty Images

Most Britons will not know these workers were asylum seekers. In fact, few residents in Dover ever see those who arrive by boat. Those who come on inflatable craft are almost always intercepted at sea. Border Force officials take them to a cavernous building behind barbed wire on a wharf near the cruise ship terminal, where they are put on buses before being housed around the country.

What people see, however, is footage of young men being taken into asylum-seeker hotels. The latest statistics show that 73 per cent of asylum seekers are male. Only 7 per cent are, like Rishan, females aged 17 and under.

Another thing has changed over a decade. There were 25,771 applications from asylum seekers in the United Kingdom in the year to June 2015. There were 111,084 in the year to June 2025 – including 43,600 who came by boat.

The debate in the UK now echoes the arguments in Australia over the past two decades, including concerns that the numbers are rising too fast and claims that the country cannot control its borders. British Prime Minister Keir Starmer says he wants to smash the people-smuggling business, while Conservative Party leader Kemi Badenoch talks tough even though her party was in power for 14 years and did not stop the boats.

Loading

Reform UK leader Nigel Farage, meanwhile, borrows directly from Australian policy. He vows to turn away those who arrive by boat, build detention centres and send some of the asylum seekers to Ascension Island in the Atlantic.

At the same time, the country is told it needs 31,000 nurses to fill vacant posts in the public health system. Rishan is one of them, thanks to her perseverance and the “do-gooders” who helped her.

“That’s the potential,” she says. “If you provide the support for young people, and anyone who comes here, then we do so much.”

Get a note directly from our foreign correspondents on what’s making headlines around the world. Sign up for our weekly What in the World newsletter.